Galicia (Spain)

| Galicia | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| — Autonomous Community — | |||

| Comunidade Autónoma de Galicia (Galician) Comunidad Autónoma de Galicia (Spanish) Autonomous Community of Galicia |

|||

|

|||

| Anthem: Os Pinos | |||

|

|||

| Coordinates: | |||

| Country | Spain | ||

| Capital | Santiago de Compostela | ||

| Provinces | A Coruña, Lugo, Ourense, Pontevedra | ||

| Government | |||

| - Type | Devolved government in a constitutional monarchy | ||

| - Body | Xunta de Galicia | ||

| - President | Alberto Núñez Feijóo (PP) | ||

| Area | |||

| - Total | 29,574.4 km2 (11,418.7 sq mi) | ||

| Area rank | 7th | ||

| Highest elevation | 2,127 m (6,978 ft) | ||

| Population (2009) | |||

| - Total | 2,796,089 | ||

| - Rank | 5th | ||

| - Density | 94.5/km2 (244.9/sq mi) | ||

| Demonym | Galician galegos (m), galegas (f) gallegos (m), gallegas (f) |

||

| Area code | +34 98- | ||

| ISO 3166 code | ES-GA | ||

| Statute of Autonomy | 1936 28 April 1981 |

||

| Official languages | Galician and Spanish | ||

| Patron Saint | St. James (25 July) | ||

| Legislature | |||

| Parliament | 75 deputies | ||

| Congress | 25 deputies (out of 350) | ||

| Senate | 19 senators (out of 264) | ||

| Website | www.xunta.es | ||

- This article is about the region in Spain. For the Polish-Ukrainian region, see Galicia (Eastern Europe).

Galicia[1] (Spanish pronunciation: [ɡaˈliθja]) is an autonomous community and historic region in northwest Spain, with the status of a historic nationality, and descends from one of the first kingdoms of Europe,[2] the Kingdom of Galicia. It is constituted under the Galician Statute of Autonomy of 1981. Its component provinces are A Coruña, Lugo, Ourense and Pontevedra. It is bordered by Portugal to the south, the Spanish regions of Castile and León and Asturias to the east, the Atlantic Ocean to the west, and the Bay of Biscay to the north.

Besides its continental territory, Galicia includes the archipelagos of Cíes, Ons, Sálvora, as well as Cortegada Island, the Malveiras Islands, Sisargas Islands, and Arousa Island.

Galicia has roughly 2.78 million inhabitants as of 2008, with the largest concentration in two coastal areas, from Ferrol to A Coruña in the northwest from Vilagarcía to Vigo on the southwest. The capital is Santiago de Compostela, in the province of A Coruña. Vigo, in the province of Pontevedra, is the most populous city, with 297,332 inhabitants (INE 2009).

Galicia has its own historic language, Galician, which is related to Portuguese since the Middle Ages. Although essentially derived from Latin, Galician has significant Celtic and Germanic content. Particular features are the extended use of the "solidarity pronoun", inexistence of perfect tenses, and the "verb answer" instead of "yes/no answer". There is similarity with Irish English on these facts.

Contents |

Toponym

The name Galicia comes from the Latin name Gallaecia, associated with the name of the ancient Celtic tribe that resided above the Douro river, the Gallaeci or Callaeci in Latin, and Kallaikói (καλλαικoι) in Greek (as mentioned by Herodotus). Gallaic was the archaic Q-Celtic language spoken by Gallaeci of the Hallstatt culture.

The name has been related to the Celtic goddess Cailleach, so the ancient galicians were described as "worshippers of Cailleach".

Geography

Galicia has a surface area of 29,574 square kilometres (11,419 sq mi).[3] Its northermost point, at 43º 47' N, is Estaca de Bares, (also the northernmost point of Spain); its southernmost, at 41º 49' N, is on the Portuguese border in the Baixa Limia-Serra do Xurés Natural Park.[3] The easternmost longitude is at 6º 42' W on the border between the province of Ourense and the Castilian-Leonese province of Zamora) its westernmost at 9º 18' W, reached in two places: the La Nave Cape in Fisterra (also known as Finisterre), and Cape Touriñán, both in the province of A Coruña.[3]

Topography

The interior of Galicia is composed of relatively low mountains without sharp peaks. There are many rivers, most (though not all) running down relatively gentle slopes in narrow river valleys, though at times their courses become far more rugged as in the canyons of the Sil river, Galicia's second most important river after the Miño.

Topographically, a remarkable feature of Galicia is the presence of many firth-like inlets along the coast, estuaries that were drowned with rising sea levels after the ice age. These are called rías and are divided into the smaller Rías Altas ("High Rías"), and the larger Rías Baixas ("Low Rías"). The Rías Altas include Ribadeo, Foz, Viveiro, Barqueiro, Ortigueira, Cedeira, Ferrol, Betanzos, A Coruña, Corme e Laxe and Camariñas. The Rías Baixas, found south of Fisterra, include Corcubión, Muros e Noia, Arousa, Pontevedra and Vigo. The Rías Altas can sometimes refer only to those east of Estaca de Bares, with the others being calld Rías Medias ("Intermediate Rías").

Erosion by the Atlantic Ocean has contributed to the great number of capes. Besides the abovementioned Estaca de Bares in the far north, separating the Atlantic Ocean from the Cantabrian Sea, other notable capes are Cape Ortegal, Cape Prior, Punta Santo Adrao, Cape Vilán, Cape Touriñán (westernmost point in Galicia), Cape Finisterre or Finestra, considered by the Romans (along with Finistère in Brittany and Land's End in Cornwall to be the end of the known world.

All along the Galician coast are various archipelagos near the mouths of the rías. These archipelagos provide protected deepwater harbors and also provide habitat for seagoing birds. A 2007 inventory estimates that the Galician coast has 316 archipelagos, islets, and freestanding rocks.[6] Among the most important of these are the archipelagos of Cíes, Ons, and Sálvora. Together with Cortegada Island, these make up the Atlantic Islands of Galicia National Park. Other significant islands are Islas Malveiras, Islas Sisargas, and Arousa Island.

The coast of this green corner of the Iberian Peninsula—some 1,500 km (930 mi) in length—is promoted for touristic purposes as "A Costa do Marisco" ("The Seafood Coast" in Galician). The spectacular landscapes and wildness of the coast attract great numbers of tourists.

Galicia's principal mountain ranges are O Xistral (northern Lugo), the Serra dos Ancares (on the border with León and Asturias), O Courel (on the border with León), O Eixo (the border between Ourense and Zamora), Macizo de Manzaneda (in the center of Ourense province), O Faro (the border between Lugo and Pontevedra), Cova da Serpe (border of Lugo and A Coruña), Montemaior (A Coruña), Montes do Testeiro (between Pontevedra and Ourense), and finally A Peneda, O Xurés and O Larouco, all on the border of Ourense and Portugal.

The mountains in Galicia are midly high and have served to isolate the rural population and discourage development of the interior. There is a ski resort in Cabeza de Manzaneda (1,778 metres, 5,833 ft) in Ourense Province. The highest mountain is Trevinca (2127 m, 6978 ft) on the eastern border of Ourense with León and Zamora provinces (which are in the autonomous community of Castile and León). Other tall peaks are Peña Survia (2095 m, 6873 ft), Alto do Torno (1942 m, 6371 ft), Maluro (925 m, 3035 ft), and Os Ancares (821 m, 2694 ft).[7]

Hydrography

Galicia has so many small rivers that it has been called the "land of the thousand rivers". The most important of the rivers are the Miño and the Sil, which has a spectacular canyon. Most of the rivers in the interior are tributaries of the Miño. Other rivers run directly to the Atlantic Ocean or the Cantabrian Sea. Most of these have short courses, especially those that run to the Cantabrian Sea.

Galicia's many hydroelectric dams take advantage of the steep, deep, narrow rivers and their canyons. Few of Galicia's rivers are navigable, other than the lower portion of the Miño and the portions of various rivers that have been dammed into reservoirs. Some rivers are navigable by small boats in their lower reaches: this is taken great advantage of in a number of semi-aquatic festivals and pilgrimages.

Environment

Galicia has preserved some of its dense Atlantic forests where wildlife is commonly found. It is relatively unpolluted, and its landscape composed of green hills, cliffs and rias is very different from what is commonly understood as Spanish landscape.

Inland Galicia is less populated, having lost people due to migration to the coast and to the major cities of Spain. The terrain is made up of several low mountain ranges crossed by many small rivers.

Galicia has had some environmental problems in the modern age. Deforestation is a problem in many areas, as is the continual spread of the eucalyptus tree, imported for the paper industry. Fauna, most notably the European Wolf, have suffered because of the actions of livestock owners and farmers. The native deer species have declined because of hunting and development. Recently, oil spills have become a major issue, especially with the Mar Egeo disaster in A Coruña and the Prestige oil spill in 2002, a crude oil spill larger than the Exxon Valdez disaster in Alaska.

Flora

Galicia is one of the more forested areas of Spain, and the majority of Galicia's forests are entirely without any formal management.[8] Galicia's forests hold many important native species of plants.

Many oak forests (known locally as fragas) remain, particularly in the north-central part of the province of Lugo and the north of the province of A Coruña (Fragas do Eume). Wood and wood products (particularly softwood pulp figure significantly in Galicia's economy. There is also some farming, both crops for direct use and pasture for livestock.

Apart from forests, Galicia is also notable for the extense surface occupied by meadows used to feed an important animal husbandry (especally [cattle]).

- Reforesting with eucalyptus (especially Eucalyptus globulus), beginning in the Franco era, largely on behalf of the paper company ENCE in Pontevedra, who wanted it for its pulp. Eucalyptus is considered a non-native species.

Fauna

Galicia has 262 inventoried species of vertebrates, including 12 species of freshwater fish, 15 amphibians, 24 reptiles, 152 birds and 59 mammals.[9]

The animals most often thought of as being "typical" of Galicia are the livestock raised there. The Galician Pony is native to the region, as is the Galician Blond cow and the domestic fowl known as the gallina de Mos. The latter is an endangered species, although it is showing signs of a comeback since 2001.[10]

Galicia's forests and mountains are home to rabbits, hares, wild boars and roe deer, all of which are popular with hunters.

Several important bird migration routes pass through Galicia, and some of the community's relatively few environmentally protected areas are Special Protection Areas (such as on the Ría de Ribadeo) for these birds.

From a domestic point of view, Galicia has been credited for author Manuel Rivas as the "land of one million cows". Galician Blond and Holstein cattles coexist on meadows and farms.

Climate

Galicia is a perfect example to describe Oceanic climate, with mild temperatures and usual rainfall throughout the year. Santiago de Compostela, for example, has an average of 100 days of rain a year. The interior, specifically the more mountainous parts of Ourense and Lugo, receive significant freezes and snowfall during the winter months.

In the summer, Galicia receives many tourists from other parts of Spain who state they are running away from hot temperatures.

History

| History of Galicia | |

|---|---|

This article is part of a series |

|

| Prehistoric Galicia | |

| Gallaeci (Celtic tribe) | |

| Roman Gallaecia | |

| Suebi Kingdom | |

| Brythonic Galicia | |

| Kingdom of Galicia | |

| The Compostela's Era | |

| Galician Modern Age | |

| Galicia in the 20th century | |

| Galicia at Present | |

|

Galicia Portal |

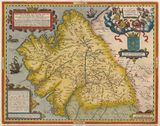

Prehistory

The Eirós Cave in the municipality of Triacastela (province of Lugo) preserves animal remains and Neanderthal stone objects from the Middle Paleolithic, thanks to its alkaline chemistry. There are other remnants of the Middle Paleolithic along the lower Miño and in the Ourense depression.

The earliest culture of the region to leave significant architectural traces appears to have been centered around veneration of the dead as intermediaries between deities and the living. The society seems to have been organized in a clan structure. Thousands of Megalithic tumuli[11] throughout the territory. Within each tumulus is a stone burial chamber known as a dolmen; the sizes of these chambers vary.

Rich mineral deposits led to the development of Bronze Age metallurgy. Utensils and gold and bronze jewelry from Galicia have been found as far away as the far side of the Pyrenees.

At this time, climate change seems to have driven migration into the region from the vast plateau of Iberia's Meseta Central, increasing the population and causing conflict between communities. Before the Roman invasion, a series of tribes lived in the region, and according to Strabo, Pliny, Herodotus and others, they shared similar Celtic customs.

Castro culture

The castro culture flourished in the second half of the Iron Age; it was a fusion of Bronze Age culture with later developments, and overlapped into the Roman era. One possibility is that the rise of this culture derives from the arrival of the Celts, who introduced new techniques of raising livestock, introduced the domesticated horse and probably introduced the grain rye. The earliest known Celtic settlement in Galicia was that of the Saefs in the 11th century BCE.[12] They conquered the Oestrymnio.[12] They brought new religious beliefs, political organization, and maritime relations extending as far as the British Isles. They were capable fighters; Strabo described them as the most difficult foes the Romans encountered in conquering Lusitania.

The castros date from this era. These were circular hill forts with multiple concentric walls. Usually there was a trench in front of each wall. Major castros were built in the coastal regions of Fazouro, Santa Tegra, Baroña and O Neixón, and in the interior at Castromao and Viladonga.

One temple survives from this culture, at Elviña near the city of A Coruña. The castro at Meirás conserves a necropolis. Other castros from the Sorotaptic culture have small boxlike structures with ashes from cremations and urn burials. There are also other structures, partially underground, with a container for water, where vestiges of fire indicate that these were the crematoria.

From the end of the Megalithic era there are inscriptions on granite (petroglyphs) in open air, but their origin and significance is unknown. The best known of these are at Campo Lameiro.

Roman rule

The Roman legions first entered the area under Decimus Junius Brutus in 137–136 BC,[13] but the province was only superficially Romanized by the time of Augustus. The Romans were interested in Galicia mainly for its mineral resources. It was made a province under the name Gallaecia. Under Roman rule, the castros lost their defensive value. The Romans brought new technologies, new travel routes, new forms of organizing property, and a new language, though they found a fierce oposition from the local inhabitants. This led to a slighter "Romanization" than other regions suffer, as well as difficulting the arrival of Christianism.

Middle Ages

During the invasions of the 5th century, Galicia fell to the Suevi in 411, who formed the first medieval kingdom to be created in Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire. In 584, the Visigothic King Leovigild invaded the Suebic kingdom of Galicia and defeated it, bringing it under Visigoth control. During this period a British colony-bishopric was established in Northern Galicia (Britonia) populated by Briton immigrants escaping the Anglo-Saxon invasion (see Mailoc). During the Moorish invasion of Spain (711-718), the Moors never managed to have any real control over Galicia, and this situation remained unchanged up until 739 when Alfonso I of Asturias successfully drove them out of Galicia; and the region was finally assimilated for good to the Kingdom of Asturias. This era consolidated Galicia as a Christian kingdom speaking a Romance language. In the 9th century, the rise of the cult of the Apostle James in Santiago de Compostela gave Galicia a particular symbolic importance among Christians, an importance it would hold throughout the Reconquista. As the Middle Ages went on, Santiago became a major pilgrim destination and the Way of Saint James a major pilgrim road, a route for the propagation of Romanesque art and the words and music of the troubadors.

During the 9th and 10th centuries, the counts of Galicia gave fluctuating obedience to their nominal sovereign, and Normans/Vikings occasionally raided the coasts. The Towers of Catoira[14] (Pontevedra) were built as a system of fortificati ons to stop the Viking raids on Santiago de Compostela.

In 1063, Ferdinand I of Castile divided his kingdom among his sons. Galicia was allotted to Garcia II of Galicia. In 1072, it was forcibly reannexed by Garcia's brother Alfonso VI of Castile, and from that time Galicia remained part of the Kingdom of Castile and Leon, although under varying degrees of self-government.

In the 13th century Alfonso X of Castile standardized the Castilian language and made it the language of court and government.

Modern era

In the dynastic conflict between Isabella I of Castile and Joanna La Beltraneja, who was believed to be the illegitimate daughter of Beltrán and the former queen, most of the Galician aristocracy supported Joanna. After Isabella's victory, she initiated the "Doma y Castración del Reino de Galicia", that is, the "Taming and Castration of the Kingdom of Galicia" (Court Historian, Zurita), a process of centralisation.

In the face of this development, the Galician language began a slow decline that would culminate in the Séculos Escuros ("Obscure Centuries"), roughly the 16th through mid-18th centuries, when written Galician practically disappeared, and the language survived only orally, marginalizing Galician-speakers.

During the Peninsular War, Galicia was one of the most affected regions. However, organisation between local people and the British Army led to a very short six-month period of French control.

The 1833 territorial division of Spain put a formal end to the Kingdom of Galicia, unifying Spain into a single centralized monarchy. Instead of seven provinces and a regional administration, Galicia was reorganized into the current four provinces. Although it was recognized as a "historical region", that status was strictly honorific. In reaction, Galician regionalist and federalist movements arose.

The liberal General Miguel Solís Cuetos led a separatist coup attempt in 1846 against the authoritarian regime of Ramón María Narváez. Solís and his forces were defeated at the Battle of Cacheiras, 23 April 1846, and the survivors, including Solís himself, were shot. They have taken their place in Galician memory as the Martyrs of Carral or simply the Martyrs of Liberty.

Defeated on the military front, Galicians turned to culture. The Rexurdimento focused on recovery of the Galician language as a vehicle of social and cultural expression. Among the writers associated with this movement are Rosalía de Castro, Manuel Murguía, Manuel Leiras Pulpeiro, and Eduardo Pondal.

In the early 20th century came another turn toward regionalist/federalist politics with Solidaridad Gallega (1907–1912) modeled on Solidaritat Catalana in Catalonia. Solidaridad Gallega failed, but in 1916 Irmandades da Fala ("Brotherhood of the Language") developed first as a cultural association but soon as a full-blown nationalist movement. Vicente Risco and Ramón Otero Pedrayo were outstanding cultural figures of this movement, and the magazine Nós ('Us'), founded 1920, its most notable cultural institution; Lois Peña Novo the outstanding political figure.

The Second Spanish Republic was declared in 1931. During the republic, the Partido Galeguista (PG) was the most important of a shifting collection of Galician nationalist parties. Following a referendum on a Galician Statute of Autonomy, Galicia was granted the status of an autonomous region. However, because of the Spanish Civil War, this was never put into practice.

Galicia was spared the worst of the fighting in that war. It was one of the areas where the initial coup attempt at the outset of the war was successful, and it remained in Nationalist hands throughout the war. While there were no pitched battles, there was repression and even death: all political parties were abolished, as were all labor unions and Galician nationalist organizations. Galicia's statute of autonomy was annulled (as were those of Catalonia and the Basque provinces once those were conquered). According to Carlos Fernández Santander, at least 4,200 people were killed either extrajudicially or after summary trials. Victims included the civil governors of all four Galician provinces; Juana Capdevielle, the wife of the governor of La Coruña; mayors such as Ángel Casal of Santiago de Compostela; prominent socialists such as Jaime Quintanilla in Ferrol and Emilio Martínez Garrido in Vigo; Popular Front deputies Antonio Bilbatúa, José Miñones, Díaz Villamil, Ignacio Seoane, and former deputy Heraclio Botana); soldiers who had not joined the rebellion, such as Generals Rogelio Caridad Pita and Enrique Salcedo Molinuevo and Admiral Antonio Azarola; and the founders of the PG, Alexandre Bóveda and Víctor Casas.[15] Many others managed to escape into exile.

General Francisco Franco — himself a Galician from Ferrol — ruled as dictator from the civil war until his death in 1975. Franco's centralizing regime suppressed any official promotion of the Galician language, although its everyday use was never proscribed. Among the attempts at resistance were small leftist guerrilla groups such as those led by José Castro Veiga ("El Piloto") and Benigno Andrade ("Foucellas"), both of whom were ultimately captured and executed.[16][17] In the 1960s, ministers such as Manuel Fraga Iribarne introduced some reforms allowing technocrats affiliated with Opus Dei to modernize administration in a way that facilitated capitalist economic development. However, for decades Galicia was largely confined to the role of a supplier of raw materials and energy to the rest of Spain, causing environmental havoc and leading to a wave of migration to Venezuela and to various parts of Europe. Fenosa, the monopolistic supplier of electricity, built hydroelectric dams, flooding many Galician river valleys.

The Galician economy finally began to modernize with a Citroën factory in Vigo, the modernization of the canning industry and the fishing fleet, and eventually a modernization of small peasant farming practices, especially in the production of cows' milk. In Orense province (now Ourense), businessman and politician Eulogio Gómez Franqueira gave impetus to the raising of livestock and poultry by establishing the Cooperativa Orensana S.A. (Coren).

During the last decade of Franco's rule, there was a renewal of nationalist feeling in Galicia. The early 1970s were a time of unrest among university students, workers, and farmers. In 1972, general strikes in Vigo and Ferrol cost the lives of Amador Rey and Daniel Niebla.[18] That same year, the bishop of Mondoñedo-Ferrol, Miguel Anxo Araúxo Iglesias, wrote a pastoral letter that was not well received by the Franco regime, about a demonstration in Bazán (Ferrol) where two workers died.[19]

As part of the transition to democracy upon the death of Franco in 1975, Galicia regained its status as an autonomous region within Spain with the Statute of Autonomy of 1981, which begins, "Galicia, historical nationality, is constituted as an Autonomous Community to access to its self-government, in agreement with the Spanish Constitution and with the present Statute (...)". Varying degrees of nationalist or independentist sentiment are evident at the political level. The only nationalist party of any electoral significance, the Bloque Nacionalista Galego or BNG, is a conglomerate of left-wing parties and individuals that claims Galician political status as a nation.

From 1990 to 2005, Manuel Fraga, former minister and ambassador in the Franco regime, presided over the Galician autonomous government, the Xunta de Galicia. Fraga was associated with the Partido Popular (PP, 'People's Party', Spain's main national conservative party) since its founding. In 2002, when the oil tanker Prestige sank and covered the Galician coast in oil, Fraga was accused by the grassroots movement 'Nunca Mais' of having been unwilling to react. In the 2005 Galician elections, the 'People's Party' lost its absolute majority, though remaining (barely) the largest party in the parliament, with 43% of the total votes. As a result, power passed to a coalition of the Partido dos Socialistas de Galicia (PSdeG) ('Galician Socialists' Party'), a regional sister-party of Spain's main social-democratic party, the Partido Socialista Obrero Español (PSOE, 'Spanish Socialist Workers Party') and the nationalist Bloque Nacionalista Galego (BNG). As the senior partner in the new coalition, the PSdeG nominated its leader, Emilio Perez Touriño, to serve as Galicia's new president, with Anxo Quintana, the leader of BNG, as its vice-president.

In 2009 the PSdG-BNG coalition lost the elections and the government went back to the People's Party, which will enjoy a comfortable majority until 2013. Alberto Núñez Feijóo (PP) is now Galicia's president.

Government and politics

Regional government

| Galicia |

This article is part of the series: |

|

|

|

Statute of Autonomy

Executive

Legislative

Judiciary

Elections

Divisions

|

|

Other countries · Atlas |

Galicia has partial self-governance, in the form of a devolved government, established on 16 March 1978 and reinforced by the Galician Statute of Autonomy, ratified on 28 April 1981. There are three branches of government: the executive branch, the Xunta de Galicia, consisting of the President and the other independently elected councillors;[20] the legislative branch consisting of the Galician Parliament; and the judicial branch consisting of the High Court of Galicia and lower courts

Executive

The Xunta de Galicia is a collective entity with executive and administrative power. It consists of the President, a vice president, and twelve councillors. Administrative power is largely delegated to dependent bodies. The Xunta also coordinates the activities of the provincial councils (deputaciones).

The President of the Xunta directs and coordinates the actions of the Xunta. He or she is simultaneously the representative of the autonomous community and of the Spanish state in Galicia. He is a member of the parliament and is elected by its deputies and then formally named by the monarch of Spain.

Legislative

The Galician Parliament[21] consists of 75 deputies elected by universal adult suffrage under a system of proportional representation. The franchise includes even Galicians who reside abroad. Elections occur every four years.

The last election of 2 May 2009 resulted in the following distribution of seats:

- Partido Popular de Galicia (PPdeG): 38 deputies (47.11%)

- Partido Socialista de Galicia (PSdeG-PSOE): 25 deputies (29.92%)

- Bloque Nacionalista Galego (BNG): 12 deputies (16.58%)

Judicial

National government

Galicia's interests are represented at national level by 25 deputies in the Congress of Deputies and 19 senators in the Senate.

Administrative divisions

Prior to the 1833 territorial division of Spain Galicia was divided into seven administrative provinces:[22]

- A Coruña

- Santiago

- Betanzos

- Mondoñedo

- Lugo

- Ourense

- Tui

From 1833, the seven original provinces of the 15th century were consolidated into four:

- A Coruña,

- Ourense,

- Pontevedra, and

- Lugo.

.svg.png) A Coruña |

.svg.png) Lugo |

.svg.png) Ourense |

.svg.png) Pontevedra |

Galicia is further divided into 53 comarcas, 315 municipalities and 3,778 parishes. Municipalities are divided into parishes, which may be further divided into aldeas ("villages") or lugares ("places"). This traditional breakdown into such small areas is unusual when compared to the rest of Spain. Roughly half of the named population entities of Spain are in Galicia, which occupies only 5.8 percent of the country's area. It is estimated that Galicia has over a million named places, over 40,000 of them being communities.[23]

The main cities are Vigo, A Coruña, Ourense, Lugo, Pontevedra, Ferrol and Santiago de Compostela, the capital and archiepiscopal seat. The main metropolitan areas are A Coruña-Ferrol in the north and Vigo-Pontevedra in the south.

Economy

Galicia is a land of economic contrast. While the western coast, with its major population centers and its fishing and manufacturing industries, is prosperous and increasing in population, the rural hinterland—the provinces of Ourense and Lugo—are economically dependent on traditional agriculture, based on small landholdings called minifundios. However, the rise of tourism, sustainable forestry and organic and traditional agriculture are bringing other possibilities to the Galician economy without compromising the preservation of the natural resources and the local culture.

Traditionally, Galicia depended mainly on agriculture and fishing. Reflecting that history, the Community Fisheries Control Agency, which coordinates fishing controls in European Union waters is based in Vigo. Nonetheless, today the tertiary sector of the economy (the service sector) is the largest, with 582,000 workers out of a regional total of 1,072,000 (as of 2002).

The secondary sector (manufacturing) includes shipbuilding in Vigo and Ferrol, textiles and granite work in A Coruña. A Coruña also manufactures automobiles, but not nearly on the scale of the automoblie manufacturing in Vigo. The Centro de Vigo de PSA Peugeot Citroën, founded in 1958 makes about 450,000 vehicles a year (455,430 in 2006);[25] a Citroën C4 Picasso made in 2007 was their nine-millionth vehicle.[24]

Arteixo, an industrial municipality in the A Coruña metropolitan area, is the headquarters of Inditex, Europe's largest textile company and the world's second largest. Of their eight brands, Zara is the best-known; indeed, it is the best-known Spanish brand of any sort on an international basis.[26] For 2007, Inditex had 9,435 million euros in sales for a net profit of 1,250 million euros.[27] The company president, Amancio Ortega, is the richest person in Spain[28] with a net worth of 21.5 billion euros.[29]

Galicia is home to savings banks Caixa Galicia and Caixanova, and to Spain's two oldest commercial banks Banco Etcheverría (the oldest) and Banco Pastor.

Galicia was late to catch the tourism boom that has swept Spain in recent decades, but the coastal regions (especially the Rías Baixas and Santiago de Compostela) are now significant tourist destinations. In 2007 5.7 million tourists visited Galicia, an 8 percent growth over the previous year, and part of a continual pattern of growth in this sector.[30] 85 percent of touristas who visit Galicia visit Santiago de Compostela.[30] Tourism constitutes 12 percent of the Galician GDP and employs between 12 and 13 percent of the regional workforce.[30]

Language

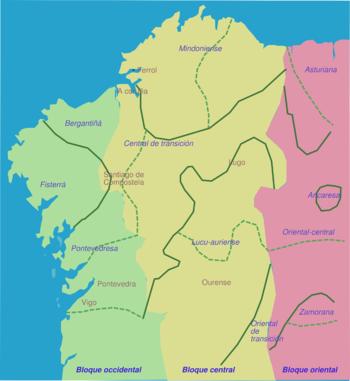

Galicia has two official languages: Galician (Galician: Galego) and Spanish (known in Spain as castellano, "Castilian"). Galician is recognized in the Statute of Autonomy of Galicia as the lingua propia (a term comparable to "mother language") of Galicia.

Galician is related to Portuguese. Both descend from a Romance language of the Middle Ages now referred to as Galician-Portuguese. The independence of Portugal since the late Middle Ages has favored the divergence of the Galician and Portuguese languages. [31]

The official Galician language has been standardized by the Real Academia Galega on the basis of literary tradition. Although there are local dialects, Galician media conform to this standard form, which is also used in primary, secondary, and university education. There are more than three million Galician speakers in the world,[31] placing Galician just barely among the 150 most widely spoken languages on earth.[3]

Castilian Spanish was nonetheless the only official language in Galicia for more than four centuries. Over the many centuries of Castilian domination, Galician faded from day-to-day use in urban areas. The period since the re-establishment of democracy in Spain—in particular since the Ley de Normalización Lingüística ("Law of Linguistic Normalization", Ley 3/1983, 15 June 1983)—represents the first time since the introduction of mass education that a generation has attended school in Galician. (Spanish is also still taught in Galician schools.)

Nowadays, Galician is resurgent, though in the cities it remains a "second language" for most. According to a 2001 census, 99.16 percent of the populace of Galicia understand the language, 91.04 percent speak it, 68.65 percent read it and 57.64 percent write it.[32] The first two numbers (understanding and speaking) remain roughly the same as a decade earlier; the latter two (reading and writing) both show enormous gains: a decade earlier, only 49.3 percent of the population could read Galician, and only 34.85 percent could write it. This fact can be easily explained because of the imposibility of teaching Galician during the Franco era, so older people speak the language but has no written competence.[32] Galician is the highest-percentage spoken language in its region among the minority languages of Spain.

The earliest known document in Galician-Portuguese dates from 1228. The "Foro do bo burgo do Castro Caldelas" was granted by Alfonso IX of Castile to the Ourensian town of Allariz.[33] A distinct Galician Literature emerged after the Middle Ages. In the 13th century, important contributions were made to the romance canon in Galician-Portuguese. The most notable were by the troubadour Martín Codax, by King Denis of Portugal and by King Alfonso X of Castile, Alfonso O Sabio ("Alfonso the Wise"), the same monarch who began the process of establishing the hegemony of Castilian. During this period, Galician-Portuguese was considered the language of love poetry in the Iberian Romance linguistic culture. The names and memories of Codax and other popular cultural figures are well preserved in modern Galicia and, despite the long period of Castilian linguistic domination, these names are again household words.

Demographics

| POPULATION OF GALICIA c. 1900 and 2006 using c. 1900 toponyms |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| A Coruña Province | |||

| District | c. 1900 pop. | 2006 pop. | |

| City of Corunna | 43,971 | 243,320 | |

| City of Ferrol (Civilian Population Only) | 25,281 | 76,399 | |

| Santiago de Compostela | 24,120 | 93,458 | |

| Towns, Villages and Hamlets | 560,184 | 716,964 | |

| All the Province (Total): | 653,556 | 1,129,141 | |

| Lugo Province | |||

| District | c. 1900 pop. | 2006 pop. | |

| City of Lugo | 26,959 | 93,450 | |

| Chantada | 15,003 | 9,249 | |

| Fonsagrada | 17,302 | 4,856 | |

| City of Mondoñedo | 10,590 | 4,770 | |

| Monforte | 12,912 | 19,412 | |

| Pantón | 12,988 | 3,147 | |

| Vilalba | 13,572 | 15,455 | |

| Viveiro | 12,843 | 15,576 | |

| Towns, Villages and Hamlets | 343,217 | 199,680 | |

| All the Province (Total): | 465,386 | 356,595 | |

| Orense Province | |||

| District | c. 1900 pop. | 2006 pop. | |

| City of Ourense | 15,194 | 108,137 | |

| Towns, Villages and Hamlets | 389,117 | 230,246 | |

| All the Province (Total): | 404,311 | 338,671 | |

| Pontevedra Province | |||

| District | c. 1900 pop. | 2006 pop. | |

| City of Vigo | 23,259 | 293,255 | |

| City of Pontevedra | 22,330 | 80,096 | |

| Towns, Villages and Hamlets | 411,673 | 569,766 | |

| All the Province (Total): | 457,262 | 943,117 | |

| THE FOUR PROVINCES TOGETHER (Total): | 1,980,515 | 2,776,524 | |

| c. 1900 statistics from Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911; 2006 statistics from INE |

|||

Galicia's inhabitants are called "Galicians" (in Galician galegos). For well over a century Galicia has grown more slowly than the rest of Spain, due largely to emigration to Latin America and to other parts of Spain. Sometimes Galicia has lost population in absolute terms. In 1857, Galicia had Spain's densest population and constituted 11.49 percent of the national population. As of 2007, only 6.13 percent of the Spanish population resides in the autonomous community. This is due to the diaspora galician people was forced to since the nineteenth century, first to South America and later to Central Europe. It is commonly referred that Galicians, Irish and Jewish have more inhabitants outside their territory than inside it.

| Demographic evolution of Galicia 1857–2007 in absolute numbers and as a percentage of the national population[34] |

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1857 | 1887 | 1900 | 1910 | 1920 | 1930 | 1940 | 1950 | ||||||||||||

| Population | 1,776,879 | 1,894,558 | 1,980,515 | 2,063,589 | 2,124,244 | 2,230,281 | 2,495,860 | 2,604,200 | |||||||||||

| Percentage | 11.49% | 10.79% | 10.64% | 10.32% | 9.93% | 9.42% | 9.59% | 9.26% | |||||||||||

| 1960 | 1970 | 1981 | 1991 | 1996 | 2001 | 2006 | 2007 | ||||||||||||

| Population | 2,602,962 | 2,583,674 | 2,753,836 | 2,720,445 | 2,742,622 | 2,732,926 | 2,767,524 | 2,772,533 | |||||||||||

| Percentage | 8.51% | 7.61% | 7.30% | 6.90% | 6.91% | 6.65% | 6.19% | 6.13% | |||||||||||

As of 2006, Galicia has 21 municipalities with populations over 20,000:

| City | Population | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Vigo | 295,703 | Vigo metropolitan area: 473,945. |

| A Coruña | 245,164 | A Coruña metropolitan area: 408,468. |

| Ourense | 107,186 | |

| Lugo | 95,416 | |

| Santiago de Compostela | 93,712 | Santiago de Compostela metropolitan area: 173,970. |

| Pontevedra | 80,096 | |

| Ferrol | 75,181 | |

| Vilagarcía de Arousa | 36,743 | |

| Narón | 35,664 | In Ferrol metropolitan area. |

| Oleiros | 31,694 | In A Coruña metropolitan area. |

| Carballo | 30,091 | |

| Redondela | 29,987 | In Vigo metropolitan area. |

| Arteixo | 27,713 | In A Coruña metropolitan area. |

| Ribeira | 27,181 | |

| Culleredo | 26,707 | In A Coruña metropolitan area. |

| Marín | 25,885 | |

| Cangas de Morrazo | 25,402 | In Vigo metropolitan area. |

| Ames | 24,553 | In Santiago de Compostela metropolitan area. |

| Cambre | 22,513 | In A Coruña metropolitan area. |

| Ponteareas | 22,411 | |

| Lalín | 20,867 | |

| Source: INE | ||

The proportion of foreigners is only 2.9 percent compared to a national figure of 10 percent; among the autonomous communities, only Extremadura has a lower percentage of immigrants.[35] Of the foreigners resident in Galicia, 17.93 percent are Portuguese, 10.93 percent Colombian and 8.74 percent Brazilian.[3] According to the 2006 census, Galicia has a fertility rate of 1.03 children per woman, compared to 1.38 nationally, and far below the figure of 2.1 that represents a stable populace.[36] Lugo and Ourense provinces have the lowest fertility rates in Spain, 0.88 and 0.93, respectively.[36]

Within the region, the A Coruña-Ferrol metropolitian area has become increasingly dominant in terms of population. The population of the City of A Coruña in 1900 was 43,971. The population of the rest of the province including the City and Naval Station of nearby Ferrol and Santiago de Compostela was 653,556. A Coruña's growth occurred after the Spanish Civil War at the same speed as other major Galician cities, but it was the arrival of democracy in Spain after the death of Francisco Franco when A Coruña left all the other Galician cities behind.

The rapid increase of population of Vigo, A Coruña, and to a lesser degree Santiago de Compostela and other major Galician cities, during the years that followed the Spanish Civil War during the mid 20th century occurred as the rural population declined: many villages and hamlets of the four provinces of Galicia disappeared or nearly disappeared during the same period. Economic development and mechanization of agriculture resulted in the fields being abandoned, and most of the population has moving to find jobs in the main cities. The number of people working in the Tertiary and Quaternary sectors of the economy has increased significantly.

Since 1999, the absolute number of births in Galicia has been increasing. In 2006, 21,392 births were registered in Galicia,[37] 300 more than in 2005, according to the Instituto Gallego de Estadística. Since 1981, the Galician life expectancy has increased by 5 years, thanks to a higher quality of life.[38]

- Birth rate (2006): 7.9 per 1,000 (all of Spain: 11.0 per 1,000)

- Death rate (2006): 10.8 per 1,000 (all of Spain: 8.4 per 1,000)

- Life expectancy at birth (2005): 80.4 years (all of Spain: 80.2 years)

- Male: 76.8 years (all of Spain: 77.0 years)

- Female: 84.0 years (all of Spain: 83.5 years)

- Source:[39]

Migration

Like most of Western Europe, Galicia's history has been defined by mass emigration. There was significant Galician emigration in the 19th and early 20th centuries to industrialized parts of Spain and to Latin America Argentina, Uruguay,Brazil or Cuba. One example is Fidel Castro, whose father was Galician, and mother was of Galician descent. The two cities with the greatest number of people of Galician descent outside of Galicia itself are Buenos Aires, Argentina, and nearby Montevideo, Uruguay where immigration from Galicia was so significant that Argentines and Uruguayans now commonly refer to all Spaniards as gallegos (Galicians).

During the Franco years there was a new wave of emigration out of Galicia to other European countries, most notably to France, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom. There are many expatriate communities throughout the world, and many have their own groups or clubs. Galician immigration is so widespread that websites such as Fillos de Galicia were created in order to organize and inform Galicians throughout the world.

Culture

Literature

As with many other Romance languages, Galician emerged as a literary language in the Middle Ages. However, in the face of the hegemony of Castilian Spanish, during the so-called Séculos Escuros ("Dark Centuries") it fell from literary use, revived only during the 19th century Rexurdimento with such writers as Rosalía de Castro, Manuel Murguía, Manuel Leiras Pulpeiro, and Eduardo Pondal. In the 20th century, before the Spanish Civil War the Irmandades da Fala ("Brotherhood of the Language") and Grupo Nós included such writers as Vicente Risco, Ramón Cabanillas and Castelao. Public use of Galician was largely suppressed during the Franco dictatorship but has been resurgent since the restoration of democracy. Contemporary writers in Galician include Xosé Luís Méndez Ferrín, Manuel Rivas, and Suso de Toro.

Cuisine

Galician cuisine often uses fish and shellfish. The empanada is a meat or fish pie, with a bread-like base, top and crust with the meat or fish filling usually being in a tomato sauce including onions and garlic. It has Celtic influence. Caldo Galego is a hearty soup whose main ingredients are potatoes and a local vegetable named grelo (Broccoli rabe). The latter is also employed in Lacón con grelos, a typical Carnival dish, consisting of pork shoulder boiled with grelos, potatoes and chorizo (paprika sausage). Centolla is the equivalent of King Crab. It is prepared by being boiled alive, having its main body opened like a shell, and then having its innards mixed vigorously. Another popular dish is octopus, boiled (traditionally in a copper pot) and served in a wooden plate, cut into small pieces and laced with olive oil, sea salt and pimentón (Spanish paprika). This dish is called Pulpo a la gallega or in Galician "Polbo á Feira", which roughly translates as "Octopus, Galician style". There are several regional varieties of cheese. The best known one is the so-called tetilla, named after its breast-like shape. Other highly regarded varieties include the San Simón cheese from Vilalba and the creamy cheese produced in the Arzúa-Curtis area. The latter area produces also high-quality beef. A classical dessert is filloas, crêpe-like pancakes made with flour, broth and eggs. When cooked at a pig slaughter festival, they may also contain the animal's blood. A famous almond cake called Tarta de Santiago (St. James' cake) is a Galician sweet speciality mainly produced in Santiago de Compostela.

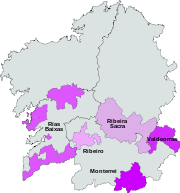

Galicia has 30 products with Denominación de Origen (D.O.), some of them with Denominación de Origen Protegida (D.O.P.).[40] D.O. and D.O.P. are part of a system of regulation of quality and geographical origin among Spain's finest producers. Galicia produces a number of high-quality wines, including Albariño, Ribeiro, Ribeira Sacra and Valdeorras. The grape varieties used are local and rarely found outside Galicia and Northern Portugal. Just as notably from Galicia comes the spirit Augardente—the name means burning water—often referred to as Orujo in Spain and internationally or as caña in Galicia. This spirit is made from the distillation of the pomace of grapes.

Sport

As in the rest of Spain, football is the most popular sport in Galicia. Deportivo de La Coruña, from the city of A Coruña, is the region's most successful club and is currently (2009–10 season) Galicia's only representative in the top flight of the national championship, La Liga. Celta de Vigo from Vigo are also a major club and are Deportivo's principal regional rivals. When the two sides play, it is normally dubbed the Galician derby. SD Compostela from Santiago de Compostela and Racing de Ferrol from Ferrol are two other notable club sides. Similarly to Catalonia and the Basque Country, Galicia also periodically fields a regional team against international opposition (see Galicia autonomous football team).

Other popular sports in Galicia include futsal (a variety of indoor football), handball and basketball. Galicia is also noted for a great tradition of acuatic sports, both in the sea and in rivers, sports such as rowing, yachting, canoeing or surfing are very popular.

Contemporary music

Pop/rock

- Los Suaves: hard rock/heavy metal band active since the early 1980s, from Ourense

- Deluxe: pop/rock band from A Coruña led by Xoel López

- Los Limones: indie rock/indie pop/post-rock group from El Ferrol led by Ferrol born Santi Santos, active since the early '80s[41]

- Siniestro Total: one of the most well-known punk bands to ever appear in Spain

- Los Piratas: pop/rock band from Vigo led by Iván Ferreiro, who started a successful solo career in 2003

- Os Resentidos: one of the most popular Galician bands of the '80s, led by Antón Reixa

- Heredeiros da Crus: the most successful rock band singing in Galician lenguage.

- Catpeople: a band based in Vigo who has been compared with Joy Division and Interpol.

Folk/traditional based music

- Luar na Lubre: band inspired in traditional Celtic music. They have colaborated with Mike Oldfield and other muscians.

- Carlos Nuñez: one of the most recognised pipers all over the world. He has also colaborated with a great number of artists, being notable his long-term friendship with The Chieftains.

- Susana Seivane: virtuous female piper. She descends from a family of pipe makers and stated she preferred pipes instead of dolls during her childhood.

- Milladoiro, Berrogüeto, Fuxan os Ventos, Cristina Pato and many others proved that galician music is in a good health.

Public Holidays

- Día de San Xosé (St. Joseph's Day) on 19 March (strictly religious)

- Día do Traballo (May Day) on 1 May

- Día das Letras Galegas (Galician Literature Day) on 17 May

- Día da Patria Galega (Galicia's National Day) also known as St. James the Apostle Day on 25 July

- Día da Nosa Señora (Day of Our Lady) on 15 August (strictly religious)

Festivals

- Festa do Corpus Christi in Ponteareas, has been observed since 1857 on the weekend following Corpus Christi (a movable feast) and is known for its floral carpets. It was declared a Festival of Touristic Interest in 1968 and a Festival of National Touristic Interest in 1980.

- Arde Lucus, in June, celebrates the Celtic and Roman history of the city of Lugo, with recreations of a Celtic weddings, Roman circus, etc.

- Rapa das Bestas ("shearing of the beasts") in Sabucedo, the first weekend in July, is the most famous of a number of rapas in Galicia and was declared a Festival of National Touristic Interest in 1963. Wild colts are driven down from the mountains and brought to a closed area known as a curro, where their manes are cut and the animals are marked, and assisted after a long winter in the hills. In Sabucedo, unlike in other rapas, the aloitadores ("fighters") each take on their task with no assistance.

- Festival de Ortigueira (Ortigueira's Festival of Celtic World) lasts four days in July, in Ortigueira. First celebrated 1978–1987 and revived in 1995, the festival is based in Celtic culture, folk music, and the encounter of different peoples throughout Spain and the world. Attended by over 100,000 people, it is considered a Festival of National Touristic Interest.

- Festa da Dorna, 24 July, in Ribeira. Founded 1948, declared a Galician Festival of Touristic Interest in 2005. Originally founded as a joke by a group of friends, it includes the Gran Prix de Carrilanas, a regatta of hand-made boats; the Icarus Prize for Unmotorized Flight; and a musical competition, the Canción de Tasca.

- Festas do Apóstolo Santiago (Festas of the Apostle James): the events in honor of the patron saint of Galicia last for half a month. The religious celebrations take place 24 July. Celebrants set off fireworks, including a pyrotechnic castle in the form of the façade of the cathedral.

- Romería Vikinga de Catoira ("Viking Pilgrimage of Catoira"), first Sunday in August, is a secular festival that has occurred since 1960 and was declared a Festival of International Touristic Interest in 2002. It commemorates the historic defense of Galicia and the treasures of Santiago de Compostela from Norman and Saracen pirate attacks.

- Feira Franca, first weekend of September, in Pontevedra recreates an open market that first occurred in 1467. The fair commemorates the height of Pontevedra's prosperigin in the 15th and 16th centuries, through historical recreation, theater, animation, and demonstration of artisanal activities. Held annually since 2000.

- Festa de San Froilán, 4–12 October, celebrating the patron saint of the city of Lugo. A Festival of National Touristic Interest, the festival was attended by 1,035,000 people in 2008.[42] It is most famous for the booths serving polbo á feira, an octopus dish.

- Festa do marisco (Seafood festival), October, in O Grove. Established 1963; declared a Festival of National Touristic Interest in the 1980s.

- Bullfighting has no thradition at all in Galicia. In fact, during the 2009 there were 8 'celebrations' out of 1848 all over Spain. In addition, recent studies have stated that 92% of Galicians are firmly against bullfighting, the highest rate of the country, even more than Catalonia. Despite this, popular associations have blamed politicians for having no compromise in order to abolish it.

Transportation

Airports

Galicia has three major airports. The most important is the Santiago de Compostela Airport, the only Galician airport with intercontinental flights. With 1,943,900 passengers in 2009, it connects to cities in Spain as well as several major European cities. Scheduled service to Caracas and Buenos Aires has been proposed. The Vigo-Peinador Airport had 1,278,762 passengers in 2008; it connects to cities in Spain and to London, Paris, and Brussels. The A Coruña Airport had 1,174,970 passengers in 2008; it connects around Spain, to Lisbon and a highly flied line to London.

Ports

The most important Galician port is the Port of Vigo, which is one of the world's leading fishing ports, with an annual catch worth 1,500 million euros.[43][44] In 2007 the port took in 732,951 metric tons (721,375 LT; 807,940 ST) of fish and seafood, and about 4,000,000 metric tons (3,900,000 LT; 4,400,000 ST) of other cargoes. Other important ports are Ferrol, A Coruña, and the smaller ports of Marín and Vilagarcía de Arousa, as well as important recreational ports in Pontevedra and Burela. Beyond these, Galicia has 120 other organized ports.

Roads

The Galician road network includes autopistas and autovías connecting the major cities, as well as national and secondary roads to the rest of the municipalities. The Autovía A-6 connects A Coruña and Lugo to Madrid, entering Galicia at Pedrafita do Cebreiro. The Autovía A-52 connects Vigo, Ourense and Benavente, and enters Galicia at A Gudiña. Two more autovías are under construction. Autovía A-8 enters Galicia on the Cantabrian coast, and ends in Baamonde (Lugo province). Autovía A-76 enters Galicia in Valdeorras; it is an upgrade of the existing N-120 to Ourense and Vigo.

Within Galicia are the Autopista AP-9 from Ferrol to Vigo and the Autopista AP-53 (also known as AG-53, because it was initially built by the Xunta de Galicia) from Santiago to Ourense. Additional roads under construction include Autovía A-54 from Santiago de Compostela to Lugo, and Autovía A-56 from Lugo to Ourense. The Xunta de Galicia has built roads connecting comarcal capitals, such as the aforementioned AG-53, or Autovía AG-55 connecting A Coruña to Carballo.

Railways

The first railway in Galicia was inaugurated 15 September 1873. It ran from O Carril, Vilagarcía de Arousa to Cornes, Conxo, Santiago de Compostela. A second line was inaugurated in 1875, connecting A Coruña and Lugo. In 1883, Galicia was first connected by rail to the rest of Spain, by way of O Barco de Valdeorras.

Galicia today has roughly 1,100 kilometres (680 mi) of rail lines. Several Iberian gauge (1,668 mm) lines operated by Adif and Renfe Operadora connect all the important Galician cities. A metre gauge (1,000 mm) line operated by FEVE connects Ferrol to Ribadeo and Oviedo. The only electrified line is the Ponferrada-Monforte de Lemos-Ourense-Vigo line. Several AVE high speed train lines are under construction. Among these are the Olmedo-Zamora-Galicia scheduled to open in 2012, which will connect Santiago and Ourense to Madrid, and the AVE Atlantic Axis route, which will connect all of the major Galician Atlantic coast cities to Portugal. Other projected AVE lines are Vigo-Monforte and A Coruña-León.

Media

Television

Televisión de Galicia (TVG) is the autonomous community's public channel, which has broadcast since 24 July 1985 and is part of the Compañía de Radio-Televisión de Galicia (CRTVG). Televisión de Galicia broadcasts throughout Galicia and has two international channels, Galicia Televisión Europa and Galicia Televisión América, available throughout the European Union and the Americas through Hispasat. CRTVG also broadcasts on DTT channel G2 and is considering adding further DTT channels, with a 24-hour news channel projected for 2010.

Radio

Radio Galega (RG) is the autonomous community's public radio station and is part of CRTVG, as is Televisión de Galicia. Radio Galega began broadcasting 24 February 1985, with regular programming starting 29 March 1985. There are two regular broadcast channels: Radio Galega and Radio Galega Música. In addition, there is a DTT and internet channel, Son Galicia Radio, dedicated specifically to Galician music.

Press

The most widely distributed newspaper in Galicia is La Voz de Galicia, with 12 local editions and a national edition. Other major newspapers are El Correo Gallego, Faro de Vigo, El Progreso (Lugo), La Región (province of Ourense), and Galicia Hoxe (The first newspaper to publish exclusively in Galician). Other newspapers of note are Atlántico Diario in the Vigo metropolitan area, the free De luns a venres (the first free daily in Galician), the sports paper DxT Campeón, El Ideal Gallego from A Coruña, the Heraldo de Vivero, the Xornal de Galicia, and the Diario de Ferrol.

Education

Galicia's education system is administered by the regional government's Ministry of Education and University Administration. 76% of Galician's youth achieve high school degree, being the fifth region of 17 with more number of successes. Galicia is situated over the years among the two or three regions with less crime rate.

University

There are three public universities in Galicia: University of A Coruña, University of Santiago de Compostela and the University of Vigo.

Notable Galicians

Image gallery

Raxó, Pontevedra |

Wall of Lugo |

Lugo Cathedral, reloxio tower |

Tower of Hercules, A Coruña |

See also

- Galician music

- Galician people

- Galician wine

- Nationalities in Spain

- Galician nationalism

- Timeline of Galician History

- Way of St. James (Camiño de Santiago)

References

- This article incorporates information from the revision as of 2010-02-15 of the equivalent article on the Spanish Wikipedia.

- This article incorporates information from the revision as of 2010-02-24 of the equivalent article on the Galician Wikipedia.

- ↑ Xesús Fraga, La Academia contesta a la Xunta que el único topónimo oficial es Galicia, La Voz de Galicia 2008-06-08.

- ↑ Historia Francorum, Gregorio de Tours

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Galicia 08, Junta de Galicia, Consejería de Cultura y Deporte.

- ↑ Rías Baixas Naturaleza, riasbaixas.depo.es, Rías Baixas Turismo (brochure).

- ↑ Cabo Touriñán es el extremo más occidental, ElCorreoGallego.es. Retrieved 2008-11-24.

- ↑ La Xunta elabora un inventario de islas para su posible compra. FaroDeVigo.es. Retrieved 2009-01-22.

- ↑ La Voz de Galicia, 10-08-2008.

- ↑ Paula Pérez, El desorden de los bosques, FaroDeVigo.es. Retrieved 2010-02-17.

- ↑ Enciclopedia Galega Universal (online version)

- ↑ La 'galiña de Mos' aumenta su censo de 100 a 5.500 ejemplares en siete años, aunque sigue en peligro de extinción, www.europapress.es, 2008-06-21.

- ↑ Antonio de la Peña Santos, Los orígenes del asentamiento humano, (chapters 1 and 2 of the book Historia de Pontevedra A Coruña:Editorial Vía Láctea, 1996. p. 23.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Juan Jesús Martín Tardío, Ponteceso (A Coruña), www.corme.net, p. 104.

- ↑ Livy lv., lvi., Epitome

- ↑ Eduardo Loureiro. "Viking Festival webpage". Catoira.net. http://www.catoira.net. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ↑ "Proposición no de ley del PSdeG-PSOE en el Parlamento de Galicia sobre Memoria Histórica" (PDF). http://www.parlamentodegalicia.es/sites/ParlamentoGalicia/BibliotecaBoletinsOficiais/B70262.pdf. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ↑ Ernesto S. Pombo, El último guerrillero antifranquista, El País, 1986-03-10. Retrieved 2010-02-18.

- ↑ Carlos Fernández, La cárcel acogió a huéspedes históricos, La Voz de Galicia, 2005-10-20. Retrieved 2010-02-18.

- ↑ María José Portero, Las huelgas más importantes, El País, 1984-03-04. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- ↑ Muere en Ourense a los 87 años el obispo emérito de Mondoñedo Miguel Anxo Araújo, La Región 2007-07-23. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- ↑ "Estatuto de Autonomía de Galicia. Título I: Del Poder Gallego". Xunta.es. 2009-10-01. http://www.xunta.es/estatuto?lang=es#T1. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ↑ "Parlamento de Galicia - By Party". Parlamento de Galicia. http://www.parlamentodegalicia.com/contenido/ING/pags/grupo_pa.htm. Retrieved 27 November 2006. "Parliament of Galicia Composition"

- ↑ The seven silver crosses on the coat of arms of Galicia refer to these seven historic provinces.

- ↑ Manuel Bragado, «Microtoponimia», Xornal de Galicia, 2005-09-05. Retrieved 2010-02-21.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Nueve millones de coches `made in´ Vigo, FaroDeVigo.es, 2007-09-12. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- ↑ Centro Vigo de PSA produjo 455.430 vehículos en 2006, el 7% más 2006-12-21. Retrieved 2010-02-18.

- ↑ Zara, la marca española más conocida en el exterior, www.finanzzas.com, 2008-04-03.

- ↑ Inditex gana un 25% más y aumentará un 15% la superficie disponible hasta 2010, www.cincodias.com, 2008-03-31.

- ↑ Amancio Ortega se refuerza en Acerinox y BBVA; entra en Iberdrola e Inbesós, Cotizalia.com, 2007-05-30.

- ↑ Amancio Ortega ya tiene 21.500 millones, El País, 2007-10-21. Retrieved 2008-11-12.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Galicia recibió un 8% más de turistas durante el 2007, LaVozDeGalicia.es, 2008-01-02. Retrieved 2008-11-03.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Galician), Ethnologue. Retrieved 2010-02-19.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Plano Xeral de Normalización da lingua galega, Xunta de Galicia. (In Galician.) p. 38.

- ↑ O Foro do bo burgo do Castro Caldelas, dado por Afonso IX in 1228, Consello da Cultura Galega. Retrieved 2010-02-19.

- ↑ Source: "Población de hecho", INE. Data comes from INE. Censo de 1857, Población de España por provincias desde 1787 a 1900, Series de población de hecho en España desde 1900 a 1991, and Series de población de España desde 1996.

- ↑ Población por nacionalidad, comunidades y provincias, sexo y edad, INE

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 As lucenses son as que menos fillos teñen en España, Galicia-Hoxe.com.

- ↑ Aumentan los nacimientos en Galicia, pero el saldo vegetativo sigue negativo, www.galiciae.com, 2005-05-28.

- ↑ Carlos Punzón, La esperanza de vida se incrementó en Galicia en cinco años desde 1981, LaVozDeGalicia.es, 2007-10-29. Retrieved 2008-11-29.

- ↑ Indicadores demográficos básicos, INE

- ↑ Denominaciones de Origen y Indicaciones Geográficas, Ministerio de Medio Ambiente y Medio Rural y Marino. Select "Galicia" in the dropdown. Retrieved 2010-02-22.

- ↑ "Los Limones del Caribe". Maketon.com. http://www.maketon.com/loslimones/biografia/151. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ↑ "O San Froilán atraeu a Lugo a máis dun millón de persoas". Elprogreso.galiciae.com. http://elprogreso.galiciae.com/nova/18491.html. Retrieved 2010-04-26.

- ↑ El Barrio Marinero, www.galiciaparaelmundo.com.

- ↑ Antoinio Figueras, ¡Y aún dicen que el pescado es caro!, weblogs.madrimasd.org/ciencia_marina

External links

- Petroglyphs from Galicia

- Irish genes from Galicia

- Walking the Camino de Santiago, A Guide The end of the Camino at Santiago and also Cape Finisterre

- Galicia's National Tourism Board

- Photographs of Galicia

- Videos from Galicia

- Rural tourism in Galicia

- Photograph of forest fire in Galicia

- Landscape photographs of Galicia

|

|||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

|

|||||||

|

|||||||